Hail Columbia!

The ‘Remembering Columbia’ Museum tour takes visitors on a journey through Columbia’s first historical flight of STS-1 through its last mission of STS-107.

It also provides a glimpse of the recovery of Columbia and the crew of STS-107, along with the two volunteers who lost their lives in the recovery efforts.

JUMP TO A SECTION: Missions | STS-107 Crew | Mission Highlights | Search and Recovery | Columbia Accident Investigation | Local Media Coverage

Space Shuttle Columbia Missions

Columbia (OV-102), the first of NASA’s orbiter fleet, made its maiden voyage on April 12, 1981.

It proved the operational concept of a winged, re-usable spaceship by successfully completing the Orbital Flight Test Program missions STS-1 through STS-4.

Click these links for information on each of Columbia’s 28 missions:

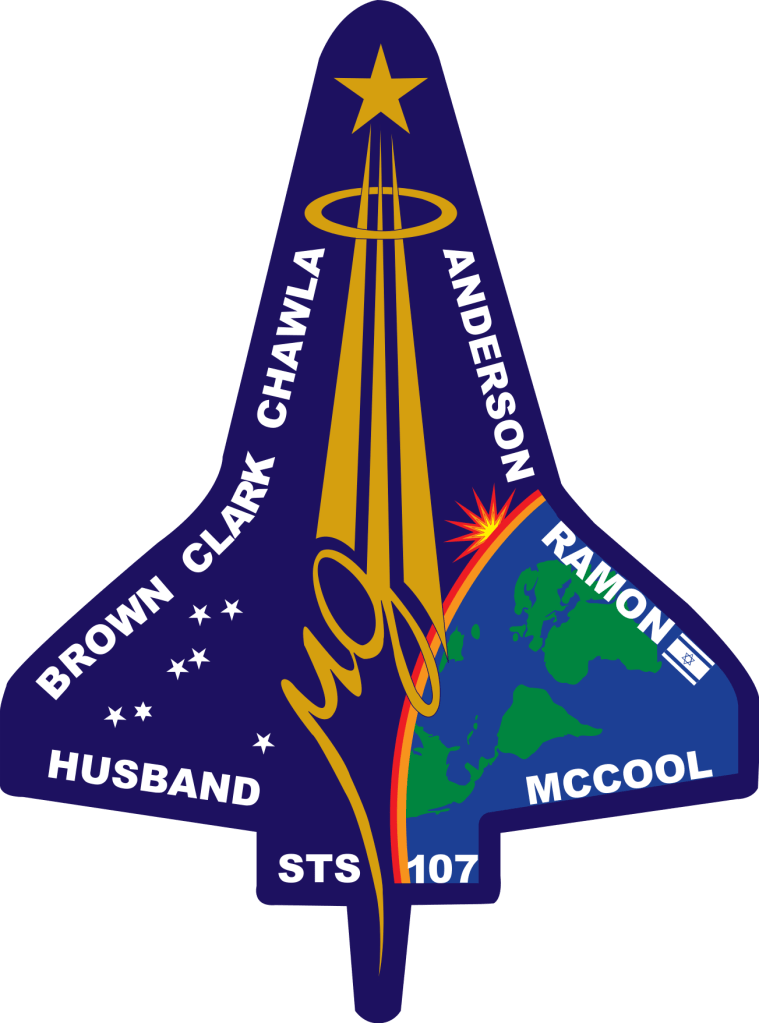

The STS-107 Crew

The first shuttle mission in 2003, STS-107 mission marked the 113th flight overall in NASA’s Space Shuttle program and the 28th flight of the Space Shuttle Orbiter Columbia.

While en route to landing at Kennedy Space Center on Feb. 1 after a 16-day mission, Columbia and crew were lost during reentry over east Texas at about 8 a.m. CST, 16 minutes prior to the scheduled touchdown at KSC.

- Rick D. Husband, Commander

Read bio → - William C. McCool, Pilot

Read bio → - David M. Brown, Mission Specialist

Read bio → - Kalpana Chawla, Mission Specialist

Read bio → - Laurel B. Clark, Mission Specialist

Read bio → - Michael P. Anderson, Payload Commander

Read bio → - Ilan Ramon, Payload Specialist of the Israeli Space Agency

Read bio →

STS-107 Mission Highlights

As a research mission, the crew was kept busy 24 hours a day performing various chores involved with science experiments.

Experiments in the SPACEHAB RDM included nine commercial payloads involving 21separate investigations, four payloads for the European Space Agency with 14 investigations, one payload/investigation for ISS Risk Mitigation and 18 payloads supporting 23 investigations for NASA’s Office of Biological and Physical Research (OBPR).

In the physical sciences, three studies inside a large, rugged chamber examined the physics of combustion, soot production and fire quenching processes in microgravity. These experiments provided new insights into combustion and fire suppression that cannot be gained on Earth.

An experiment that compresses granular materials in the absence of gravity furthered our understanding of construction techniques. This information can help engineers provide stronger foundations for structures in areas where earthquakes, floods and landslides are common.

Another experiment evaluated the formation of zeolite crystals, which can speed the chemical reactions that are the basis for chemical processes used in refining, biomedical and other areas. Yet another experiment used pressurized liquid xenon to mimic the behaviors of more complex fluids such as blood flowing through capillaries.

In the area of biological applications, two separate OBPR experiments allowed different types of cell cultures to grow together in weightlessness to elevate their development of enhanced genetic characteristics — one use was to combat prostate cancer, the other to improve crop yield. Another experiment evaluated the commercial usefulness of plant products grown in space.

A facility for forming protein crystals more purely and with fewer flaws than is possible on Earth may lead to a drug designed for specific diseases with fewer side effects.

A commercially sponsored facility housed two experiments to grow protein crystals to study possible therapies against the factors that cause cancers to spread and bone cancer to inflict intense pain on its sufferers.

A third experiment looked at developing a new technique of encapsulating anti-cancer drugs to improve their efficiency.

Other studies focused on changes, due to space flight, in the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems; in the systems which sense and respond to gravity; and in the capability of organisms to respond to stress and maintain normal function.

NASA also tested a new technology to recycle water prior to installing a device to recycle water permanently aboard the International Space Station.

The European Space Agency (ESA), through a contract with SPACEHAB, flew an important payload focused on astronaut health, biological function and basic physical phenomena in space. These experiments addressed different aspects of many of the same phenomena that NASA is interested in, providing a more thorough description of the effects of space flight, often in the same subjects or specimens.

ESA performed seven in-flight experiments, and one ground-based, on the cardiopulmonary changes that occur in astronauts.

Additional ESA biological investigations examined bone formation and maintenance; immune system functioning; connective tissue growth and repair; and bacterial and yeast cell responses to the stresses of space flight.

A special facility grew large, well-ordered protein and virus crystals that were expected to lead to improved drug designs. Another studied the physical characteristics of bubbles and droplets in the absence of the effects of Earth’s gravity.

SPACEHAB was also making it possible for universities, companies and other government agencies to do important research in space without having to provide their own spacecraft.

The Canadian Space Agency sponsored three bone-growth experiments, and was collaborating with ESA on two others.

The German Space Agency measured the development of the gravity-sensing organs of fish in the absence of gravity.

A university was growing ultra-pure protein crystals for drug research. And another university was testing a navigation system for future satellites.

The U.S. Air Force was conducting a communications experiment. Students from six schools in Australia, China, Israel, Japan, Liechtenstein and the United States were probing the effects of space flight on spiders, silkworms, inorganic crystals, fish, bees and ants, respectively.

There were also experiments in Columbia’s payload bay, including three attached to the top of the RDM: the Combined Two-Phase Loop Experiment (COM2PLEX), Miniature Satellite Threat Reporting System (MSTRS) and Star Navigation (STARNAV).

There were six payloads/experiments on the Hitchhiker pallet — the Fast Reaction Experiments Enabling Science, Technology, Applications and Research (FREESTAR), which was mounted on a bridge-like structure spanning the width of the payload bay. These six investigations looked outward to the Sun, downward at Earth’s atmosphere and inward into the physics of fluid phenomena, as well as tested technology for space communications.

FREESTAR held the Critical Viscosity of Xenon- 2 (CVX-2), Low Power Transceiver (LPT), Mediterranean Israeli Dust Experiment (MEIDEX), Space Experiment Module (SEM- 14), Solar Constant Experiment-3 (SOLCON-3) and Shuttle Ozone Limb Sounding Experiment (SOLSE-2). The SEM was made up of 11 separate student experiments from schools across the U.S. and was the 14th flight of a SEM on the space shuttle.

Additional secondary payloads were the Shuttle Ionospheric Modification with Pulsed Local Exhaust Experiment (SIMPLEX) and Ram Burn Observation (RAMBO).

During the debris recovery activities, some of the Columbia experiments were found. Scientists have indicated valuable science will still be produced. Much of the scientific data was transmitted to experimenters on the ground during the flight.

Search and Recovery

Immediately after the accident, authorities in East Texas and Louisiana began the arduous task of recovering the remains of the astronauts and the debris from Columbia, a process that took more than three months and resulted in the recovery of about 38% of Columbia by weight, more than 40 tons of material.

A massive team of professionals and volunteers — more than 25,000 people from 270 organizations helped search 2.3 million acres, contributing more than 1.5 million hours toward the recovery.

What followed was the largest ground search in U.S. history. The people of East Texas, joined by volunteers from around the country, made it their mission to bring Columbia home.

The city of Hemphill and Sabine County proved to be one of the key

search areas for the Columbia wreckage. The partial remains of all seven crew

members were found within Sabine County. Pastor Fred Raney accompanied the FBI

evidence recovery team and conducted a “chapel in the woods” memorial service

for each astronaut. Search crews also found Columbia’s orbiter experiments recorder, a tape recorder that stored key data about the shuttle’s performance during re-entry. This “black box” provided key evidence for accident investigators. One of the largest and most recognizable pieces of Columbia—the 500-pound nose cone—was recovered here. The community considers this place hallowed ground.

Estimates are that the population of Hemphill tripled during the event. With only five restaurants in town, locals still provided more than 3,000 free meals a day over 15 days for workers engaged in the search and related activities.

Debris was returned to a hangar at Kennedy Space Center during the Columbia Accident Investigation.

Today, more than 80,000 pieces are housed in the Columbia Research and Preservation area, a nearly 7,000-square-foot room located on the 16th floor of the “A” Tower of the Vehicle Assembly Building.

NASA provides Columbia debris material for research to the aerospace and educational industry.

Columbia Accident Investigation

A seven month long investigation into the accident revealed that a piece of light-weight insulating foam had punctured the Reinforced Carbon Carbon thermal shield on the left wing of Shuttle Columbia during launch on January 16, 2003. The breach in the thermal protection system led to catastrophic failure of Columbia at approximately 200,000 feet altitude and a speed of Mach 18.

For additional research information on Columbia’s final mission, STS-107, please visit these NASA sites:

- History; Remembering Columbia

- Space Flight Archives; STS-107

- STS-107 Shuttle Mission Archives

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board Report

- Columbia Crew Survivability Report

Local Media Coverage

Local news station KTRE has compiled an archive of their coverage of the Space Shuttle Columbia since 2003. Click here to read more.